Find us at mvzarchives.berkeley.edu!

We will continue to share stories and news from the MVZ Archives at our new address.

Our principal website at MVZ and Ecoreader for field notebook access remains the same, too.

While rehousing the Benjamin Hoag papers, I came across some field notes wrapped in a piece of paper. The Hoag papers date from 1878-1916. The wrapping paper looks to have notes written by Milton Ray, an ornithologist and oologist whose papers also reside at the MVZ. I assume that the Hoag egg collection was bought by Ray and then later donated to the MVZ.

What’s interesting is that on the back of Ray’s notes is a schedule of sessions dated September 11-12, 1942. It is titled, “San Francisco Plant and Building Protection School, Sponsored by the San Francisco Civilian Defense council, Assisted by the San Francisco Bay Region Metropolitan Defense Council.” The series of talks took place at the Fairmont Hotel. The field notes wrapped inside date back to 1889.

This little piece of San Francisco WWII history is a gem within a gem. The sessions listed are humbling to think about (e.g. “Effect of Aerial Bombardment”). Ray’s scratch paper is a snap shot of some of the defense efforts organized in San Francisco and who would of thought something like this would be in the MVZ Archives?!!!

Written by URAP Sierra Abasolo, a third-year history major participating in the IMLS, “Strategic Stewardship for Sustaining the Archives of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology” project. Spring semester 2018.

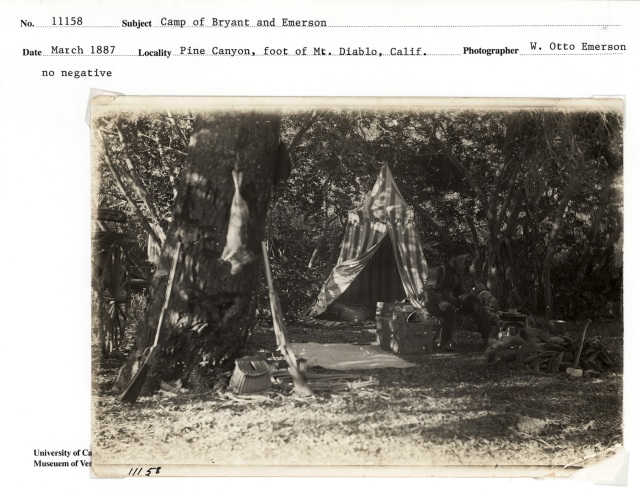

This photo (MVZ 11158) was captured by Otto Emerson near the base of Mount Diablo in Pine Canyon. The photo shows the camp of Walter E. Bryant and Otto W Emerson in March of 1887. Emerson was known for collecting environmental samples as a sort of hobby of his, so these men may have been out to expand their research.

This photo stood out to me as I was sorting through hundreds of photos because of the extravagant looking tent in the background that caught my attention. The tall stripped tent that comes to a point at the top reminded me of a circus tent. Another aspect I found striking about this photo is how old it is. Most of the photos I have seen are around 1913 or later, but this one was taken in 1887. I was surprised that a photo could have survived over 130 years, and considering photography was not used in the United States until late in the Antebellum period (1812 – 1860).

Another reason I was drawn to this photo was because it was taken at the base of Mount Diablo which is my favorite mountain because I could see it every time I looked out my window. My dad and I also hiked around the base of the mountain several years ago, so I thought it was cool to see such an old photo of one of my favorite places. Also, I plan on climbing to the top with my dad in the next few years.

Written by URAP Lorena Zeferino, a third year MCB Neurobiology student participating in the IMLS, “Strategic Stewardship for Sustaining the Archives of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology” project.

Photo taken by L.V. Compton, Point Lobos, Monterey County, California, 1934, MVZ 7238

Ever since I was a young child, I always had a love for animals and while looking through the MVZ archive, I was delighted by L.V Compton’s photographs of California’s adorable little thief; the raccoon. Raccoons are a species that is found commonly throughout Northern California and usually can live in farmlands, urban cities and suburban towns. I am from southern California where the raccoon population is particularly abundant since raccoons are attracted to urban cities such as Los Angeles and suburban areas such as Orange County. L.V Compton’s photographs are extraordinary visual captures of raccoons, since these creatures are nocturnal, they use their distinct black masks as a way to reduce glare that helps them visualize better in the dark therefore photographs of raccoons in daylight is a rare chance. Raccoons are also fiercely independent and are known to depart from their mother just after one year of age and due to their highly adaptive nature, it is very common to find a single raccoon burrowing through the trashcans of someone’s home looking for any meal to fulfil their omnivore diet.

Photo taken by L.V. Compton, Point Lobos, Monterey County, California, 1934, MVZ 7238.

L.V Compton’s photographs show a raccoon concentrating on the water which is a usual behavior for this creature. Although raccoons are known to dig into trash in order to find leftovers to feed on, raccoons use water to wash their found meal to reduce bacteria. It can be inferred that these photographs display this common behavior. Raccoons are a unique species but they are not to be considered to be potential pets since they will exhibit wild nature as well as being a heavy carrier of diseases that can be fatal to humans. These creatures will continue to express their wild nature even after being “tamed” therefore raccoons are to remain the nocturnal animals of the wild however L.V Compton’s photograph can be a slight glance into raccoon’s behavior towards their environment.

Written by Helen Yang, a fourth year student participating in the IMLS, “Strategic Stewardship for Sustaining the Archives of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology” project.

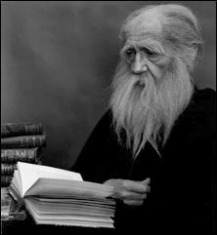

Richard “Dick” Marshall Eakin was a professor in the zoology department at UC Berkeley. He became an instructor in 1936 after having received his PhD at UC Berkeley as well. In 1970, concerned with the decreasing attendance levels in his class, he came up with the idea of giving lectures dressed as historical scientists. His first impersonation was of William Harvey – the scientist who discovered the circulatory system – and involved a cow’s heart and tomato juice to simulate blood. He was dedicated to making his performances realistic and engaging, investing in drama classes, makeup artists, wigs and props. A typical course’s lineup would include William Harvey, William Beaumont, Hans Spemann, Gregor Mendel, Louis Pasteur, and Charles Darwin.

Richard M. Eakin, dressed as Charles Darwin. Photo by O. P. Pearson, 1971.

Needless to say, Eakin’s performances generated much attention throughout the years. His impersonation lectures were extraordinarily well-attended; even faculty and students who were not in the course would attend, filling the room so that people had to stand in the aisles. He was featured in publications internationally and guest lectured in universities nationwide. Photos and text from his lectures were compiled into a book called Great Scientists Speak Again. In his own words, “If I, acting as the professor, tell them the facts, I can impart knowledge. But when the people of science come before them and use the same words, they have more meaning.”

He wasn’t just known for being a character (or several) – he was a well-respected researcher who published many studies on reptiles and amphibians, with a particular interest in embryology, photoreceptors, and the parietal eye. Over the years he received a whole host of awards and recognition, including the Berkeley Citation, one of the highest awards given to Berkeley faculty. He helped tremendously in building up Berkeley’s zoology department, including serving as department chair for over 10 years, helping to establish field stations and research laboratories, and publishing an account called History of Zoology at Berkeley. As such, he had a healthy correspondence with the MVZ, spanning from 1934 to 1981 and concerning all manner of zoology-related business. He died in 1999, but his legacy lives on in his publications, his correspondences, and the impact he had on the lives of his students.

References:

“Richard Marshall Eakin.” SF Gate, http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Richard-Marshall-Eakin-2892225.php (accessed 17 April 2017).

Sanders, Robert. “Richard M. Eakin, a zoology professor who enthralled UC Berkeley students with costumed lectures, is dead at 89.” University of California, Berkeley, http://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/99legacy/12-01-1999b.html (accessed 17 April 2017).

Written by Salaam Sbini, a fourth year history student participating in the IMLS, “Strategic Stewardship for Sustaining the Archives of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology” project.

One can imagine having an interest in something that tends to move, breathe, and live. Maybe an organism of some sort, or an interest in something possibly more abstract, but nonetheless in existence. George G. Simpson’s interest was in both. Considered the most influential paleontologist of the twentieth century, Simpson’s area of study was not only restricted to the study of fossils and mammals which roamed the earth thousands of years ago, but also in evolutionary biology.

Simpson in 1965. https://www.nceas.ucsb.edu/~alroy/lefa/Simpson.html

George G. Simpson combined paleontology into the modern Synthetic Theory of Evolution. Attempting to utilize fossil records “as a sampling of ancient breeding populations,” thus creating an exciting reemergence of the paleontology field, and adding a component of evolutionary biology. Simpson was president of the Society for the Study of Evolution, and communicated with Alden H. Miller (director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the time) through one of the correspondence letters, to create and establish a journal for the field of evolution. The letter was dated the same year as the organization itself was just established. The journal was quickly established the following year. A man of many talents, scientific rigor, and obvious accomplishments in different respected fields, George Simpson was a trailblazer. No biography of himself or his work could better attest except that of Eugene Raymond Hall’s (curator and at times acting director of MVZ) letter to Simpson in 1942 that simply included, “as always, your productivity is a stimulus to those of us who do not get quite so much done as yourself.”

References:

McFadden, Robert D. “George G. Simpson, 82, Dies; A Vertebrate Paleontoglogist.” The New York Times. 1984. http://www.nytimes.com/1984/10/08/obituaries/george-g-simpson-82-dies-a-vertebrate-paleontologist.html

Stephen Jay Gould Archive. “S.J.G. Archive: People: G.G. Simpson.” Biography Sketch. http://www.stephenjaygould.org/people/george_simpson.html

Written by Salaam Sbini, a fourth year history student participating in the IMLS, “Strategic Stewardship for Sustaining the Archives of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology” project.

Every so often I go through a correspondence file that goes beyond the United States’ borders and territories. Dr. Vladimir Evgenevich Sokolov’s file was a correspondence that was a reminder of America’s relations past its domestic realm, its relations with the formerly named USSR, and its pursuit of education. The first of the correspondence letters was a detailed itinerary report for Dr. Sokolov’s visit to the United States in 1965, including a long stay at the University of California Berkeley, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ). This itinerary was put together and sent by the “Committee on Friendly Relations Among Foreign Students,” an organization that facilitated international students, scholars, and professors visits and stays at universities and educational institutions – now known as the International Student Service.

Vladimir Evgenevich Sokolov: 1928-1998 American Society of Mammalogists http://www.jstor.org/stable/1383187

Dr. Sokolov was a pioneer in the environmental movement in Russia, and one of Russia’s first global sustainability advocates. Taking after his father, a zoology professor, Dr. Sokolov was a zoologist and renown leader in mammalogy. His area of expertise was on the form and functions of mammalian skin. His published works from Moscow State University and his general dissertation work from the Moscow Fur Institute in 1953 became internationally acclaimed. An ardent internationalist, he organized grouped zoological excursions with different foreign scientific organizations in different parts of the world. In 1965, Dr. Sokolov began his first organized visits to the United States, touring Washington D.C., Yale, New York, Minneapolis, Missoula, to the West Coast, Seattle, San Francisco, Utah, Los Angeles. His arrangements orchestrated through “Inter-University Committee on Travel Grant” on behalf of UC Berkeley and other universities such as UCLA, Harvard, and Yale with the presence of a representative of the Soviet Ministry of Higher Education.

The letters, including details of travel reports, government regulation citations of Soviet scholarly visits, and caution of visa disapproval that are requested by the Soviet Union were a reflection of the turbulent times between the USSR and the United States. The year of Dr. Sokolov’s visit was when President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered american troops into Vietnam. The year before was the fall of Khrushchev, two years before that was the infamous Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Yet with the political climate and sociopolitical occurrences that took shape in 1965, there was a push to bring Dr. Sokolov to the MVZ and have him share his scholarly expertise to students across the country. This was a moment of transcending propaganda and politics, in exchange of intellectual discussion and discoveries. May we all push toward human progress and scientific discovery.

References:

Shishkin, Vladimir S., and Robert S. Hoffmann. “Vladimir Evgenevich Sokolov: 1928-1998.” Journal of Mammalogy 80, no. 4 (1999): 1361-364. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1383187.

https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/pubs/fs/85895.htm#troops_to_vietnam

Written by Helen Yang, a fourth year student participating in the IMLS, “Strategic Stewardship for Sustaining the Archives of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology” project.

Equally as important as the researchers who study the MVZ’s specimens are the collectors who acquire these animals to make research possible in the first place. One such figure was John Peter Bollons, a sea captain, ethnographer, and naturalist from England. In his file are some of the oldest letters I’ve yet encountered – the earliest from 1923. His elegant handwriting on weathered but well-preserved paper answers a request from the MVZ’s first director, Joseph Grinnell, to obtain bird skins from New Zealand to add to our collection. (Specifically requested were Royal Albatross, Giant Fulmar, and Crested Penguin.) Although time constraints prevented Bollons from fulfilling the request, his correspondence remains in the archives as a fascinating glimpse into his life and the time period in which he lived.

Captain John Bollons. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/19356575

Bollons was known for two passions: natural history and Maori culture. This latter interest began when he was shipwrecked near Bluff Harbor and was taken in and cared for by a Maori family. Endeared by their hospitality, he decided to remain in New Zealand, working on a variety of vessels until he became captain of the government service steamer Hinemoa. He was fluent in the Maori language and loved it so much that he gave each of his eight children Maori middle names.

Throughout his life, he sailed along the coasts of New Zealand performing a variety of jobs including servicing lighthouses, charting coasts, rescuing castaways, and carrying scientific expeditions. He did his own collecting along the way; over his lifetime he amassed an impressive collection of over 5000 natural history specimens and Maori artifacts. His correspondence with MVZ continues until 1927 – just two years before his death. It inspires me that even in the end of his life, he was still doing what he loved: exploring the coasts of New Zealand.

References:

“Captain John Peter Bollons: a mariner and collector.” Museum of New Zealand, collections.tepapa.govt.nz/Topic/8178 (accessed 6 March 2017)

Gavin McLean. “Bollons, John Peter”, from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies/3b40/bollons-john-peter (accessed 6 March 2017)

Written by Salaam Sbini, a fourth year history student participating in the IMLS, “Strategic Stewardship for Sustaining the Archives of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology” project.

The brown manila folders filled with correspondence letters and photos I go through are filled with various inquiries–usually the same patterns of inquiries between the MVZ and organizations, scientists, and universities. Inquiries for different skins, animal acquirement, requests of loans, or return of loans, and conference scheduling from Paraguay to Havana, Cuba to Berkeley, California. I have the chance to look at the lives of individuals who pioneered in their field and their daily thoughts, tasks, and interests from the vantage point of a reader, decades later.

A letter from Edgar C. Schenck took me by surprise. As I went through three letters initially addressed to Joseph Grinnell, and a photo in his file, I was trying to decide if he was our usual candidate of either an ornithologist, herpetologist, biologist, or zoologist–he was none of those. Schenck was the Director of the Honolulu Academy of Arts from 1934-1947 and had his last position as the director of the Brooklyn Museum before he passed in 1959. He had a keen interest in Oriental and Polynesian art, but his life was cut short at the age of 49 from a heart attack as he was in Istanbul, Turkey returning from Pakistan.

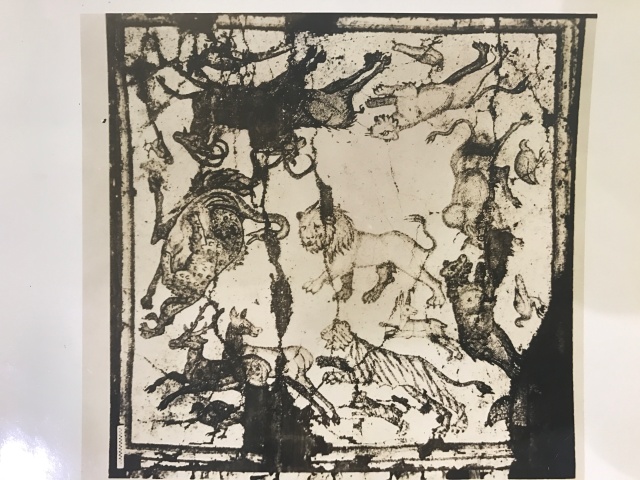

A man in the field of the fine arts, Schenck was a common contributor to publications of the Art Bulletin, the College Art Journal, and publications around archeology. This begs the questions as to why Schneck was contacting the Museum! Schenck had acquired a mosaic pavement from “Antioch, Syria,” today considered a city in modern day Turkey. Antakya is close to Syria’s border, and was considered part of the Syrian territory until 1939 when the Republic of Turkey acquired the city. The mosaic depicted a fauna of the region. Schenck was hoping Professor Grinnell would be able to identify the animals on the mosaic, their habitat, and if the depicted animals were “in or around Antioch.” Hoping to receive any available photographs of the animals from the MVZ or geographical assurance, Schenck was directed to the British Museum who was better versed in the geographic region, and because Professor Grinnell was on sabbatical.

With this correspondence we can take away that the year 1938 was a time Antioch was considered part of Syria, but also why the MVZ was contacted and used for various endeavors, even including art.

References:

“Schenck, Edgar Craig, 1909-1959,” accessed February 27, 2017, http://socialarchive.iath.virginia.edu/ark:/99166/w6sx6jqk.

“History of Antakya (Hatay), Turkey,” accessed February 27, 2017, http://www.turkeytravelplanner.com/go/med/antakya/see/history.html.